Note: The newest episode of IMBIF is out! We discussed A Canticle for Leibowitz and the episode can be found here.

A Canticle for Leibowitz by Walter Miller Jr. is a marvelous piece of science fiction. One way to tell a good book is actually a great book is that it can withstand being read at multiple levels and has a good deal of symbolism. One type of symbolism I have learned to pay attention to when reading any literature is reference to metals. In the third section, Fiat Voluntas Tua, Abbot Zerchi is speaking to Brother Joshua and compares himself and previous abbots in the Order of St. Leibowitz to various metals being tried by God:

“Listen, none of us has been really able. But we've tried, and we've been tried. It tries you to destruction, but you're here for that. This Order has had abbots of gold, abbots of cold tough steel, abbots of corroded lead, and none of them was able, although some were abler than others, some saints even. The gold got battered, the steel got brittle and broke, and the corroded lead got stamped into ashes by Heaven. Me, I've been lucky enough to be quicksilver; I spatter, but I run back together somehow. I feel another spattering coming on, though, Brother, and I think it's for keeps this time. What are you made of, son? What's to be tried?"

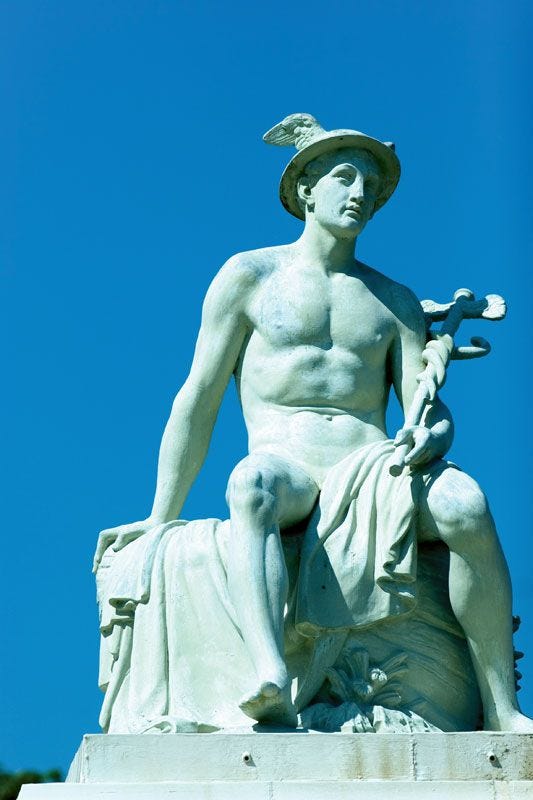

C. S. Lewis, through his book, The Discarded Image, explains that metals are connected to the planets in the cosmology of the Middle Ages. Zerchi mentions gold, steel (iron), and lead, which are related to the Sun, Mars, and Saturn, respectively. However, Zerchi compares himself to quicksilver, which is another name for mercury. Christiana Hale provides a full description of the characteristics of the planet Mercury in her book, Deeper Heaven:

“The Mercurial spirit is a difficult one to pin down — as it should be. Lewis describes the various attributes and symbols that are associated with Mercury, but he ends by simply saying: ‘It is better just to take some real mercury in a saucer and play with it for a few minutes. That is what ‘Mercurial’ means. Mercury is associated with men of action. He is the lord of language — of words and their meanings, of learning and the study of literature. Mercury is multi-faceted (‘Merry multitude of meeting selves, same but sundered’) and is associated with thieves and deceptions. Mercury was the messenger god of the Romans (to the Greeks, he was Hermes). Speed and nimbleness, both physical and intellectual, are possessed under his sway. Lewis’ best attempt at describing the unity of all these characteristics is ‘skilled eagerness’ or ‘bright alacrity.’”

There are many moments in Fiat Voluntas Tua, that Zerchi exhibits the characteristics of Mercury. So many, in fact, that Miller must have had this planet in mind when he wrote this section. I wonder if the abbots in previous sections, Arkos and Paulo, have planets associated with them? Perhaps gold/Sun in Fiat Homo for the gold-tooth and the sun-scorched desert and steel/Mars in Fiat Lux for the advent of war. Lead/Saturn could be represented in the ever-present theme of death and the merciless march of time. These are ideas to be explored some other time.

In this post, I will go through the various passages that link Zerchi to Mercury. When we are introduced to Zerchi at the beginning of Fiat Voluntas Tua, Miller gives us a direct explanation of his character:

“Like other abbots before him, the Dom Jethrah Zerchi was by nature not an especially contemplative man, although as spiritual ruler of his community he was vowed to foster the development of certain aspects of the contemplative life in this flock, and, as a monk, to attempt the cultivation of a contemplative disposition in himself. Dom Zerchi was not very good at either of these. His nature impelled him toward action even in thought; his mind refused to sit still and contemplate. There was a quality of restlessness about him which had driven him to the leadership of the flock; it made him a bolder ruler, occasionally even a more successful ruler, than some of his predecessors, but that same restlessness could easily become a liability, or even a vice.”

Zerchi is a man of action, not contemplation. He is restless and bold, which helps makes him a successful abbot. Zerchi is also impulsive, which gets him into trouble. He has an inclination to fight “unslayable dragons.” For example, Zerchi angrily tries to fix an auto-scribe, a machine that automatically translates messages into different languages. Instead of translating messages, it writes the message backwards, with random capital letters, and jumbled words. He pulls panels off to expose the wires and gives himself an electric shock, which causes his forearm to tremor.

Everything in this introduction to Zerchi is loaded with symbols pointing to Mercury. Mercurial men are driven to action as in Zerchi’s impulsive drive to fix this complicated machine (the dragon) without any forethought or training. They are connected to language and the meaning of words such as Zerchi becoming angry at the nonsense the auto-scribe produces. Mercury is also a poor conductor of electricity, hence Zerchi’s painful shock to his arm.

Mercury is evasive and hard to pin down. Zerchi’s evasiveness is the most apparent when dealing with Mrs. Grales, the two-headed tomato seller who is constantly asking him to baptize her vestigial head, Rachel. Zerchi does not want to baptize Rachel because Rachel has not shown any signs of life and he is not her parish priest. She began to explain her dealings with other priests when Brother Joshua roughly grabs Zerchi’s arm.

"What are you doing?" he whispered, but then noticed the monk's expression. Joshua's eyes were fixed on the old woman as if she were a cockatrice. Zerchi followed his gaze, but saw nothing stranger than usual; her extra head was half concealed by a sort of veil, but Brother Joshua had certainly seen that often enough.

Another word for cockatrice is a basilisk. A basilisk is a mythical animal with the front end of a chicken and tail of a reptile. It was thought to be a perverse union between the earth and the heavens. This is symbolized by Mrs. Grales selling tomatoes from the earth and her mutation being the result of nuclear bombs from the heavens. Rachel is seen as a mutation and nothing more.

The basilisk also has the ability to kill with a single glance. Rachel’s eyes are important and will come up again later. Joshua explains to Zerchi that he thought he saw Rachel smile while her eyes were still closed. Interestingly, the Grand Medieval Bestiary states that only one animal was a danger to the basilisk: the weasel. Weasels are connected to mercury given their fluid movement and association with preaching. Zerchi, here, is the weasel due to his attempts to avoid Mrs. Grales.

According to the Grand Medieval Bestiary:

Of all these small carnivores, it is the weasel that developed the richest symbolism. The moralized bestiaries claim that weasels conceived through their mouths and gave birth through their ears. This belief goes back to Anaxagoras, and Aristotle explained that it was an erroneous interpretation of seeing a weasel carrying its young in its mouth. The apparent absence of coitus for reproduction made the weasel a symbol for chastity. However, the most widespread interpretation was the one embraced by Philippe de Thaon, Guillaume le Clerc, and Pierre de Beauvais, who viewed the weasel as a symbol of successful preaching. Procreation via the mouth corresponded to the fertile speech of preachers, and childbirth through the ear referred back to conversion following the hearing of sacred instruction.

At the end of the book, Zerchi will both preach successfully and receive sacred instruction.

Later, a nuclear bomb goes off and destroys the nearby town. The survivors are all suffering from the effects of radiation poisoning, burns, and broken bones. Dr. Cors, a representative of the The Green Star, a parallel to the Red Cross, asks Zerchi if they can use the monastery grounds to give medical care to the sick and wounded. Zerchi allows this on the condition that The Green Star does not recommend or offer euthanasia to those they consider to be “hopeless cases” of radiation sickness. As Mercury is tied to words and literature, Zerchi makes Cors put his promise in writing and sign his name to it in order to further bind him to his oath.

Abbot Zerchi groped for a sharp reply, found one, but swiftly swallowed it. He searched for a blank piece of paper and a pen and pushed them across the desk. "Just write: 'I will not recommend euthanasia to any patient while at this abbey,' and sign it. Then you can use the courtyard."

"And if I refuse?"

"Then I suppose they'll have to drag themselves two miles down the road."

"Of all the merciless– "

"On the contrary. I've offered you an opportunity to do your work as required by the law you recognize, without overstepping the law I recognize. Whether they go down the road or not is up to you."

The doctor stared at the blank page. "What is so magic about putting it in writing?"

"I prefer it that way."

He bent silently over the desk and wrote. He looked at what he had written, then slashed his signature under it and straightened. "All right, there's your promise. Do you think it's worth any more than my spoken word?"

"No. No indeed." The abbot folded the note and tucked it into his coat. "But it's here in my pocket, and you know it's here in my pocket, and I can look at it occasionally, that's all. Do you keep promises, by the way, Doctor Cors?"

The medic stared at him for a moment. "I'll keep it." He grunted, then turned on his heel and stalked out.

Cors does not, in fact, keep his promise. Two patients, a mother and child, barely survived the atomic blast and had not long to live. Cors, seeing that they were both in constant pain, suggested that they kill themselves to avoid a painful death. Zerchi found out and picked them up in his car as the mother limped along the road with her child to go die at the “mercy camp.” Zerchi tries multiple methods of persuasion, changing his tactics several times. After those attempts failed, he tries something more direct.

"If I am being a little brutal," said the priest, "then it is to you, not to the baby. The baby, as you say, can't understand. And you, as you say, are not complaining. Therefore– "

"Therefore you're asking me to let her die slowly and– "

"No! I'm not asking you. As a priest of Christ I am commanding you by the authority of Almighty God not to lay hands on your child, not to offer her life in sacrifice to a false god of expedient mercy. I do not advise you, I adjure and command you in the name of Christ the King. Is that clear?"

Dom Zerchi had never spoken with such a voice before, and the ease with which the words came to his lips surprised even the priest. As he continued to look at her, her eyes fell. For an instant he had feared that the girl would laugh in his face. When Holy Church occasionally hinted that she still considered her authority to be supreme over all nations and superior to the authority of states, men in these times tended to snicker. And yet the authenticity of the command could still be sensed by a bitter girl with a dying child. It had been brutal to try to reason with her, and he regretted it. A simple direct command might accomplish what persuasion could not. She needed the voice of authority now, more than she needed persuasion. He could see it by the way she had wilted, although he had spoken the command as gently as his voice could manage.

It was only when he was direct and used words related to his priestly authority did he have any success in convincing the young mother and her child to live. As Miller stated before, Zerchi’s mercurial strength can also be a vice. Zerchi is an eloquent speaker, but his passionate speeches to the woman meant nothing to her. He could not use words to reason away her suffering or her child’s. In the end, words were still used, but in a way that purified Zerchi’s mercurial character, giving them authority and meaning to the woman who needed them. I will address the final outcome of the woman and child later on.

After it seems he has convinced the woman, Zerchi drives the woman and child around in his car completing errands. He delivers a message, discusses the refugee situation with another priest, and picks up some documents. This seems incongruous with the rest of the plot, but it is an example of Zerchi’s connection with the weasel. According to Charbonneau-Lassay in The Bestiary of Christ:

Although the Ancients classified the weasel as an inauspicious animal that one would be better off not to meet on one’s path, they did recognize its extreme familial tenderness and care in constantly moving its young so that enemies could not find them, or so that they would be better sheltered. This habitual movement from one place to another explains why certain symbolists made the weasel their allegorical image of inconstancy, but others, looking further and higher, saw in it a symbol of carefulness, vigilance, and active paternal affection.

Zerchi’s final goal was the safe delivery of the woman and child to the monastery for care and consolation. They would be sheltered and protected from the dragons.

Victory was not total. With the woman and child still in his car, he slows down to look at the Green Star “mercy camp” because he notices something is wrong. He instructed some novices to hold signs of protest in front of the camp after he had found out Cors had lied to him. The novices were no longer marching and police officers were on the scene. The officers stopped Zerchi’s car and commanded him to let the woman and child out. Cors comes out to take the child from Zerchi and brings them both back to the camp.

Cors came back through the gate. The woman and her child had been escorted into the camp area. The doctor's expression was grave, if not guilty.

"Listen, Father," he said, "I know how you feel about all this, but– "

Abbot Zerchi's fist shot out at the doctor's face in a straight right jab. It caught Cors off balance, and he sat down hard in the driveway. He looked bewildered. He snuffled a few times. Suddenly his nose leaked blood. The police had the priest's arms pinned behind him.

At this point, I should mention that Mercury is also thought to rule over the constellation Gemini, the twins Castor and Pollux. Castor was a horseman and Pollux was a boxer. Zerchi is associated with both of these figures with his car, a modern horse, and with punching Cors in the face. Cors also represents another “unslayable dragon,” a battle Zerchi cannot hope to win on his own. Zerchi, being a man of action, could not keep back from trying to prevent the woman and child from committing suicide through Cors’ assistance.

Cors does not press charges against Zerchi and he is free to go.

Disturbed by his own actions, and distraught over the fate of the two people he failed to save, Zerchi finds absolution in confession. Afterwards, he meets Mrs. Grales to hear her confession. In mercurial fashion, he has been avoiding her for some time and she finally pins him down. He is again disturbed by her choice of words. She desires to forgive God for making her what she is, a two-headed mutant.

"Shriv'ness– to Him who made me as I am," she whimpered. But then a slow smile spread her mouth. "I– I never forgave Him for it."

"Forgive God? How can you– ? He is just. He is Justice, He is Love. How can you say– ?"

Her eyes pleaded with him. "Mayn't an old tumater woman forgive Him just a little for His Justice? Afor I be asking His shriv'ness on me?"

Dom Zerchi swallowed a dry place. He glanced down at her bicephalous shadow on the floor. It hinted at a terrible Justice– this shadow shape. He could not bring himself to reprove her for choosing the word forgive. In her simple world, it was conceivable to forgive justice as well as to forgive injustice, for Man to pardon God as well as for God to pardon Man. So be it, then, and bear with her, Lord, he thought, adjusting his stole.

Mrs. Grales’ use of the word “forgive” is a signal that she has finally accepted what God has done for her in His perfect justice. It is a version of the Virgin Mary’s acceptance in Luke 1:38: “And Mary said: Behold the handmaid of the Lord; be it done to me according to thy word. And the angel departed from her.”

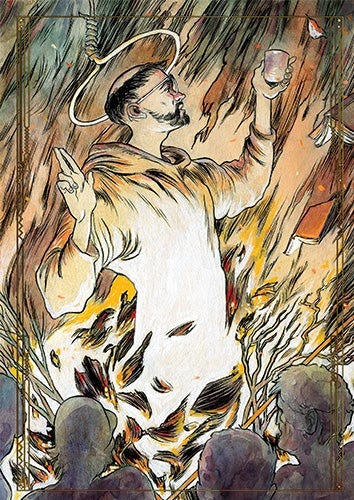

During Mrs. Grales’ confession with Zerchi, things begin to change. It is interesting to note that Zerchi, being in the spirit of Mercury, does not understand the sins Grales is confessing. He believes she is confessing to an abortion, but the text is not clear. Remember, Mercury is supposed to be linked to words and their meaning, but here the meaning is obscured. A light begins to pour into the confessional and Zerchi tells her to quickly make an Act of Contrition. Grales’ voice begins changing. The bombs are falling and God’s grace is pouring in, overshadowing Mrs. Grales. Zerchi bounds out of the confessional and grabs the ciborium filled with the Eucharist to try to protect Him from the explosion.

The building fell in on him.

When he awoke, there was nothing but dust. He was pinned to the ground at the waist. He lay on his belly in the dirt and tried to move. One arm was free, but the other was caught under the weight that held him down. His free hand still clutched the ciborium, but he had tipped it in falling, and the top had come off, spilling several of the small Hosts.

Finally, the mercurial priest has been pinned down, spattered, as he, himself, predicted at the beginning of the section. This is his final spattering. It’s for keeps this time. His arm and legs are crushed; there shall be can no running, no more evasion. Now, the quicksilver man of action is forced into contemplation.

Mercury is a transition metal, meaning that is ductile, malleable, and is able to conduct heat and electricity (albeit poorly). Zerchi is an abbot of transition as well. Not only is “Z” the final letter in the alphabet, signaling “the end,” Zerchi is also the transition abbot of the monastery as well. Brother Joshua will be splitting off from Zerchi and taking the monastery into space to both serve the people who live in the outer colonies and protect the ancient knowledge of civilization. Zerchi is also witness to the next transition of creation in the form of Rachel.

As Zerchi lays dying, pinned under the rubble of the church, the final purification process begins. Let it be for the child and her mother, then. What I impose, I must accept. Fas est. Like a good abbot, Zerchi allows his intense suffering to purify him as he told the dying mother and child. He, too must accept this. I mean Jesus never asked a man to do a damn thing that Jesus didn't do.

Bombs and tantrums, when the world grew bitter because the world fell somehow short of half remembered Eden. The bitterness was essentially against God. Listen, Man, you have to give up the bitterness– "be granting shriv'ness to God," as she'd say– before anything; before love.

But bombs and tantrums. They didn't forgive.

Zerchi hears her singing before he sees her.

"Rachel," he breathed.

"rachel," the creature answered.

She knelt there in front of him and settled back on her heels. She watched him with cool green eyes and smiled innocently. The eyes were alert with wonder, curiosity, and– perhaps something else– but she could apparently not see that he was in pain. There was something about her eyes that caused him to notice nothing else for several seconds.

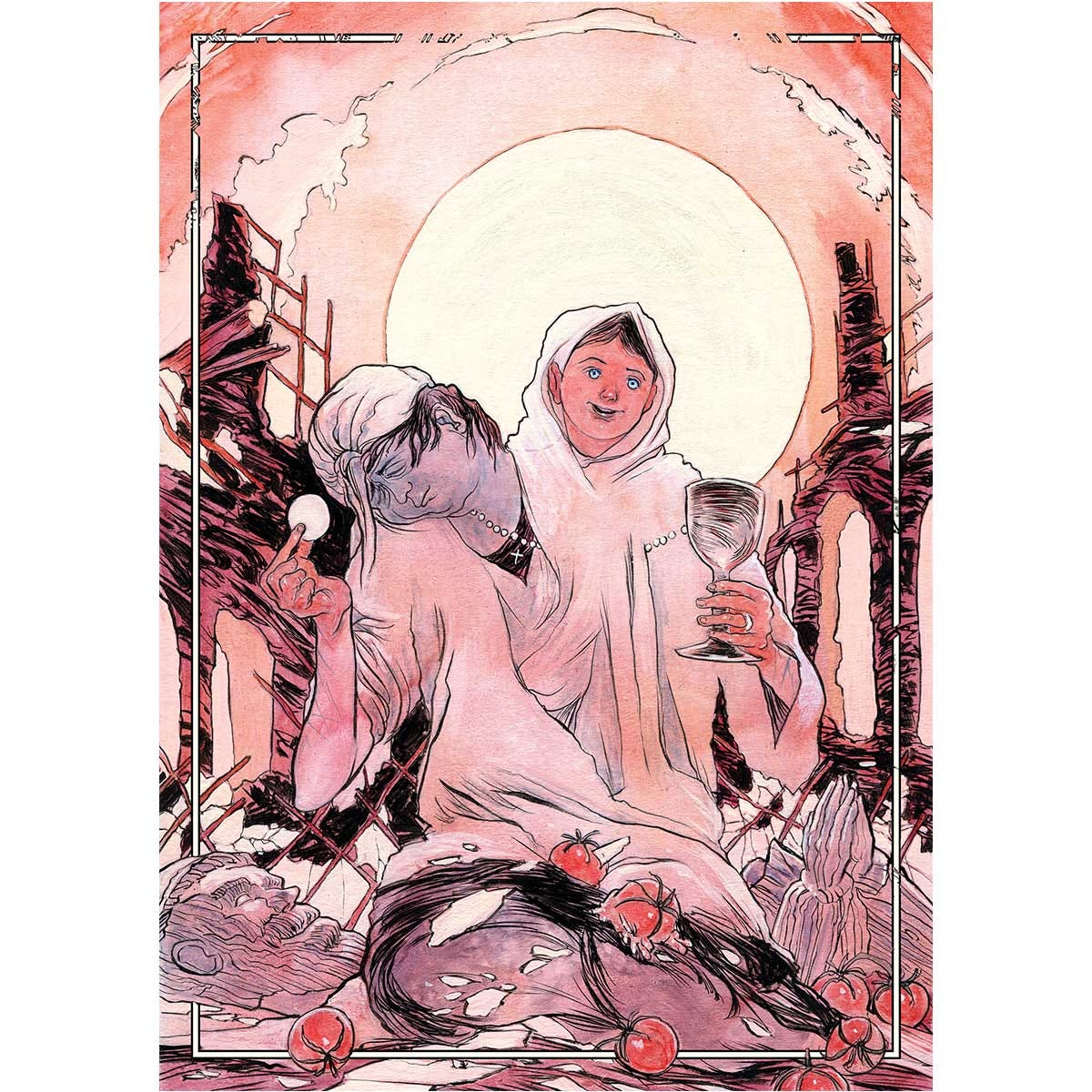

Remember, the eyes of the cockatrice or basilisk could kill with a glance. Rachel’s green eyes were not full of death, but life. She is the opposite of the monster Zerchi thought Joshua saw. Mrs. Grales’ body had been rejuvenated and now Rachel is awake and alert. Mrs. Grales appears to be dead and her head looked withered and old.

Rachel is a creature somehow born without original sin. She implicitly understands that she does not need baptism, so she flinches away when Zerchi tries to offer her a conditional one. She can sense the Presence under the veil of the bread and offers Christ to Zerchi as a form of Last Rites.

He tried to refocus his eyes to get another look at the face of this being, who by gestures alone had said to him: I do not need your first Sacrament, Man, but I am worthy to convey to you this Sacrament of Life. Now he knew what she was, and he sobbed faintly when he could not again force his eyes to focus on those cool, green, and untroubled eyes of one born free.

Since Rachel is not a basilisk after all, Zerchi, the weasel, is not her enemy. If anything, the basilisk is really Dr. Cors and his “mercy camp.” The weasel is at ease; now all that is left is one final task for Mercury. Zerchi needs to deliver a message to Rachel: The Magnificat.

"Magnificat anima mea Dominum," he whispered. "My soul doth magnify the Lord, and my spirit hath rejoiced in God my Saviour; for He hath regarded the lowliness of His handmaid. . . ."

He wanted to teach her these words as his last act, for he was certain that she shared something with the Maiden who first had spoken them. "Magnificat anima mea Dominum et exultavit spiritus meus in Deo, salutari meo, quia respexit humilitatem. . ."

He ran out of breath, before he had finished. His vision went foggy; he could no longer see her form. But cool fingertips touched his forehead, and he heard her say one word:

"Live."

Then she was gone. He could hear her voice trailing away in the new ruins. "la la la, la-la-la. . ."

Remember, the weasel is associated with successful preaching and this was Zerchi’s most successful sermon. Also like Mercury, Zerchi delivers his most important message. The weasel is also tied to conversion following the hearing of sacred instruction. Rachel tells Zerchi to “Live.” The cool, green eyes promise life and resurrection and not death, like the basilisk.

Mrs. Grales became the Holy Grail, and like Galahad, Zerchi was finally pure enough to see and touch it. The last thing he heard from Rachel was singing.

The image of those cool green eyes lingered with him as long as life. He did not ask why God would choose to raise up a creature of primal innocence from the shoulder of Mrs. Grales, or why God gave to it the preternatural gifts of Eden– those gifts which Man had been trying to seize by brute force again from Heaven since first he lost them. He had seen primal innocence in those eyes, and a promise of resurrection. One glimpse had been a bounty, and he wept in gratitude. Afterwards he lay with his face in the wet dirt and waited.

Arron, You seem to have an avocation for symbolic myths; have you thought of developing a sort of Catholic taxonomy of myths? I was thinking of even a binomial nomenclature like Linnaeus' which was intended to show the Biblical order of creation of plants and animals. My inspiration is Northrop Frye's talk, "Repetitions of Jocob's Dream" in "The Eternal Act of Creation", although Frey seems to mean creation of art from a humanist perspective, so his taxonomy is only implicit and all over the place, putting all myth-symbols on a level playing field.