Over the past 6 months, I have become a huge fan of Studio Ghibli and the director Hayao Miyazaki. This is a big change. When I was younger, I watched a number of Ghibli films and did not really like them. I thought they were disturbing and too darn weird. Well, it turns out that I actually like disturbing and weird. Disturbing and weird things tend to be decent carriers of meaning.

When Miyazaki’s newest film, The Boy and the Heron, came out in 2023, I needed to wait for it to be available for streaming. During that time, my wife and I watched Princess Mononoke, Howl’s Moving Castle, Spirited Away, Ponyo, and Porco Rosso (which was surprisingly good). I wanted to build up to watching The Boy and the Heron, which is considered the capstone of Miyazaki’s career.

The Boy and the Heron did not disappoint. I can’t say I understand a fraction of the movie, but it was definitely loaded with symbolism and subtext. I am not going to try to tackle the movie in any sort of comprehensive way; I would need to watch it a dozen more times and learn more about Japanese culture first. However, I happened to notice a lot of bird imagery, specifically, herons, pelicans, and parakeets.

I also know that herons, pelicans, and parakeets have entries in the Medieval bestiary tradition. I can already hear the critics cry fowl (get it?)! “Miyazaki is Japanese!”, they cry. “Pelicans and whatever birds won’t mean the same thing in Japanese culture as they would in Medieval Christendom!”

Well, maybe, maybe not. Honestly, I have no idea. I actually did try to research how parakeets and pelicans were used symbolically in Japanese culture, but I can up short. Either way, Miyazaki does quote Dante’s Inferno in The Boy and the Heron, so I figured he has some familiarity with Medieval European culture.

In this post, I want to briefly explore the bestiary entries for herons, pelicans, and parakeets. I don’t want to spoil anything in the movie, so I will keep references to it light and brief. For those who have seen the movie, try to think about how the following descriptions are reflected in the film, if at all. It could be that they are reversed in some cases.

Herons

The main bird in the movie is the Gray Heron voiced by Robert Pattinson in the English dub. Herons have centuries of folklore behind them in Japanese culture. Herons are associated with death, spirits, and are seen as a link to another world. They were seen as divine and able to traverse across earth, air, and water. The Grey Heron, in particular, is considered creepy or melancholy. Fortunately, someone wrote a book an entire book on the gray heron and Japanese folklore, but it appears to be only available in Japanese.

Here is a passage from Louis Charbonneau-Lassay’s The Bestiary of Christ:

The gray heron, with the penitential color of its plumage, had a particular character of melancholy in the eyes of former symbolists. Pliny had stated that this bird when oppressed by misfortune weeps tears of blood, and this connected it in their minds with the moment of Christ’s agony in Gethsemane when “his sweat was as it were great drops of blood falling down to the ground.” The heron’s preference for solitary places has also made of it one of Christian symbolism’s rare living examples of silence, a silence which is precious because it leads the human being from reflection to wisdom. Medieval artists, especially the heraldists, represented this idea by showing the heron standing and holding in its beak a stone that keeps it from uttering a sound. This stone was called by the Ancients leucochryse (white crystal), a gem of a pale golden color, traversed by white lines, which was believed to help the person who carried it to acquire wisdom.

The theme of death is very present in the movie and the Gray Heron literally tells the main character, Mahito, that he will be his guide. Very fitting so far. There is tragedy and misfortune as well. The Gray Heron is not very quiet, but there is a stone. That is all I will say.

Pelicans

As far as I can tell, pelicans are not nearly as well represented in Japanese folklore as herons. The main pelican in The Boy and the Heron is called the Noble Pelican (Willem Dafoe). Pelicans have a good reason to be noble because they are often associated with Christ.

According to St. Isidore of Seville, in his Etymologies:

The pelican is an Egyptian bird that dwells in the Nile’s desert regions…It is said, if this be true, that it kills its young, and mourns them for three days, then wounds itself and revives its children by sprinkling them with its blood.

Pelicans became linked to Christ symbolically because they inflict a wound in their side (typically on the right) with their sharp beak and douse their dead children with their own blood to bring them back to life.

It is also interesting that they sometimes kill their own children as well. Charbonneau-Lassay says:

…or it may happen that the chicks are quite lively, but that they treat the father bird shamefully, striking him in the face with their wings and beaks, so that he, justly enraged, kills them on the spot.

The connection to the death of children is worth paying attention to. The Noble Pelican explains his predicament to Mahito in the film. Perhaps the beautiful, magical world Mahito finds himself in, is not so good. It may even be cursed.

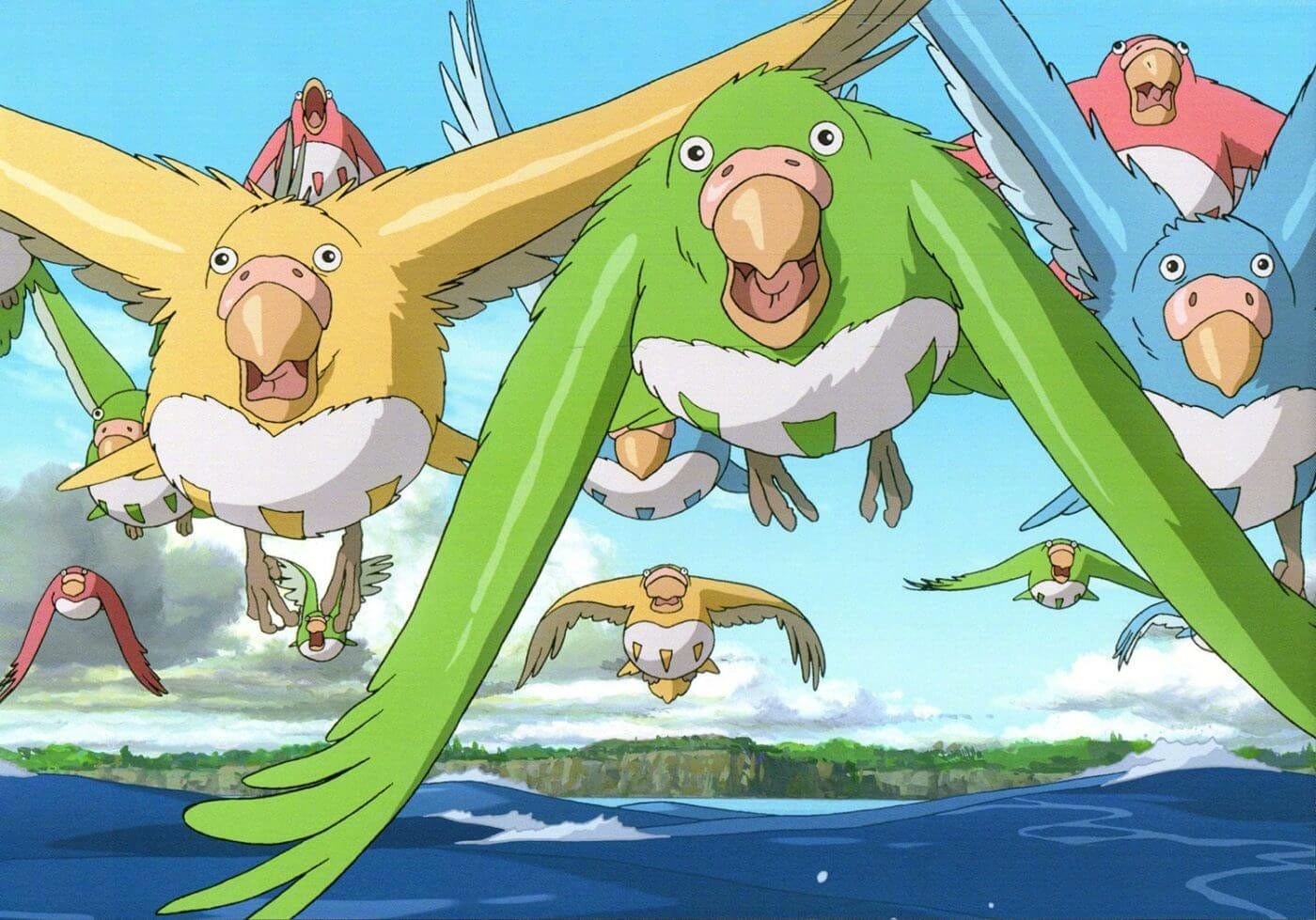

Parrots/Parakeets

Parakeets are small, colorful, seed eating birds that make good pets. Their beaks aren’t terribly strong, so their bite doesn’t hurt as much as larger parrots, and some can learn to mimic human speech. Males are usually more talkative than females because, well, they want to attract the ladies!

The Grand Medieval Bestiary says this about parakeets:

It was also appreciated for the beauty of its plumage, combined with its entertaining ability to mimic the human voice, a feat it performed far better than members of the crow family, which predominated in Europe before the importation of the first parrots and parakeets.

The bestiary goes on:

Teaching is easier when the bird is still small and in the first half of its life, when it learns faster and retains more; as it ages, it becomes forgetful and disobedient.

The ability to mimic human voices might be why Miyazaki chose to make the parakeets the closest thing to human civilization in his fantasy world. I am not the first to make this connection, but I cannot remember where I read that! His parakeets are roughly human sized, but carnivorous and bloodthirsty. Parakeets also live in flocks, making them a good choice for a community. They are easily trained when younger, but rebel as they get older.

Is this Dave Bautista’s best role? Look at that mustache!

Well, I hope this was interesting for everyone. I love the bestiary tradition and I want someone to revive it. This definitely does not exhaust the symbolism of these birds in The Boy and the Heron, but I think it sheds some light on these animals as they are depicted in the film.

Great piece here. Porco Rosso might just be my favorite Miyazaki film next to Nausicaä. Spirited Away is Miyazaki's masterpiece as a filmmaker. I like Porco Rosso because as a military historian, it's always interesting to see the interwar period in southern Europe depicted, especially with the call backs to the Italian front of WWI, or the Italo-Turkish War, and how that leads the countries into the 1920s and 30s. As the descendant of southern Italian immigrants to the US, it's an interesting look at the home country, as we start learning more and more about our past, and start to question the prevailing narratives surrounding the Risorgimento, and the "unification" of Italy (really, the war of the Savoiard Conquest). If I could change one thing about the film, I would tell Cary Elwes to just use his natural accent, and change the origin of Donald Curtis from Texan to high-class New Englander - Cary's accent reminds me of some of the old money families up there. His "Texas" accent is atrocious.

So, in my view, poetic insight into the metaphysical depths of a creature’s semiotic meaning can be true or false. There can be equivocities. I think the poet has vatic vision because caught up in the ecstasy of the other. The sophist never goes out of him or herself, never really takes in the message of the other. The result is propaganda, an egophanic screed, but not a revelation of created depths, because the mirror of the soul must be humble. An ascesis is needed for the true names to be heard and reflected in art.

Anyway, I too, am fond of Miyazaki, and the point of all this is that whether or not an artist is consciously aware, whether or not a particular meaning is congenial or not to the historical conventions of a particular culture, the deepest meanings do not merely come from a horizontal line of accrued symbolic gestures. They also come from a vertical, formal dimension that transcends those limits.

Those who decry cultural appropriation or dismiss analogies across traditions betray a positivist historicism. Time is not like that, nor is the perduring eternal care that intersects in a manner that makes possible the surmise of common discoveries a coda purely outside of time. Indeed, if the Logos is the ultimate Source of cosmic realities, it is no stretch to discern a connection between Christ and Miyazaki’s avian friends.