“Now, Master, you can dismiss your servant in peace; you have fulfilled your word. For my eyes have witnessed your saving deed, displayed for all the peoples to see: A revealing light to the Gentiles, the glory of your people Israel” (Lk 2:29-32).

It should be no surprise to anyone that the Catholic Latin Liturgy has shaped Western culture throughout the centuries. It is a well-spring of inspiration and poetry that has influenced both Catholic and non-Catholic artists. One of my favorite things about literature are the deep cut liturgical references that are hidden beneath the surface of many great novels. These references create resonances that can illuminate both the Feast and the story itself.

J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings has several famous examples. By now, every Tolkien fan knows that the Ring was destroyed in the fires of Mount Doom on March 25. Why did Tolkien select this day for the defeat of Sauron? There are multiple reasons. March 25 is the date for the Feast of the Annunciation, with which most modern Catholics will be familiar. It is also the traditional date of the Creation of the World, the Crucifixion, and others. Even without diving too deeply into the symbolism, the resonances with the destruction of the One Ring should be obvious.

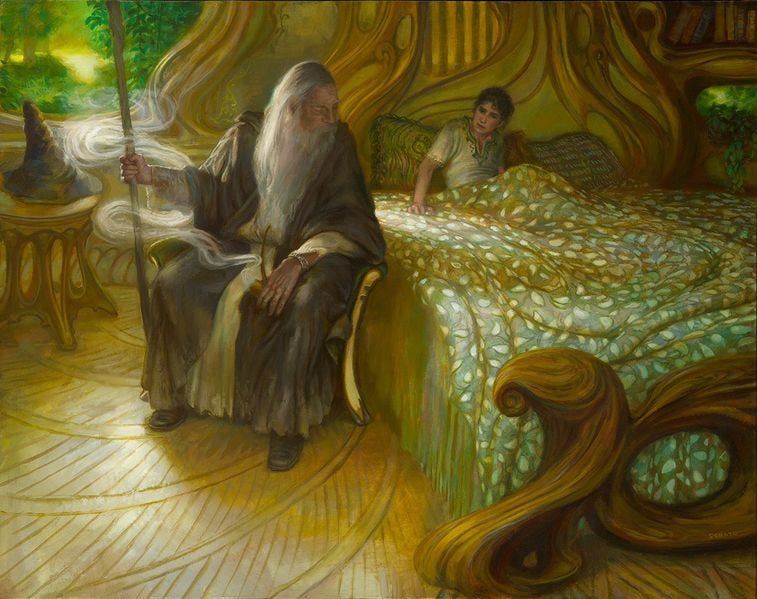

Recently, I learned that the date of Frodo’s recovery in Rivendell, October 24, is the traditional feast of St. Raphael the Archangel, patron saint of healing, travelers, and happy meetings. After his harrowing journey, Frodo wakes up in this place of healing to be reunited with his friends. After the Second Vatican Council, the feasts of Sts. Raphael, Michael, and Gabriel were combined together for The Feast of the Archangels on September 29.

(If you ask me, I think we should go back to celebrating each one separately to give them all proper respect.)

Tolkien’s examples are well known, but there is another, lesser known, author who makes good use of the liturgy in his fiction, Tim Powers. References to Christian feasts are scattered throughout Powers’ fiction, but the book I will be focusing on is The Anubis Gates.

The Anubis Gates (1983) is one of my all-time favorite books. It is a mad-cap story about time-travel, Egyptian sorcerers, and Romantic poets. It’s also about Divine Grace defeating demonic powers if you pay close attention to certain clues, especially dates. When Powers references a date, go check the liturgical calendar.

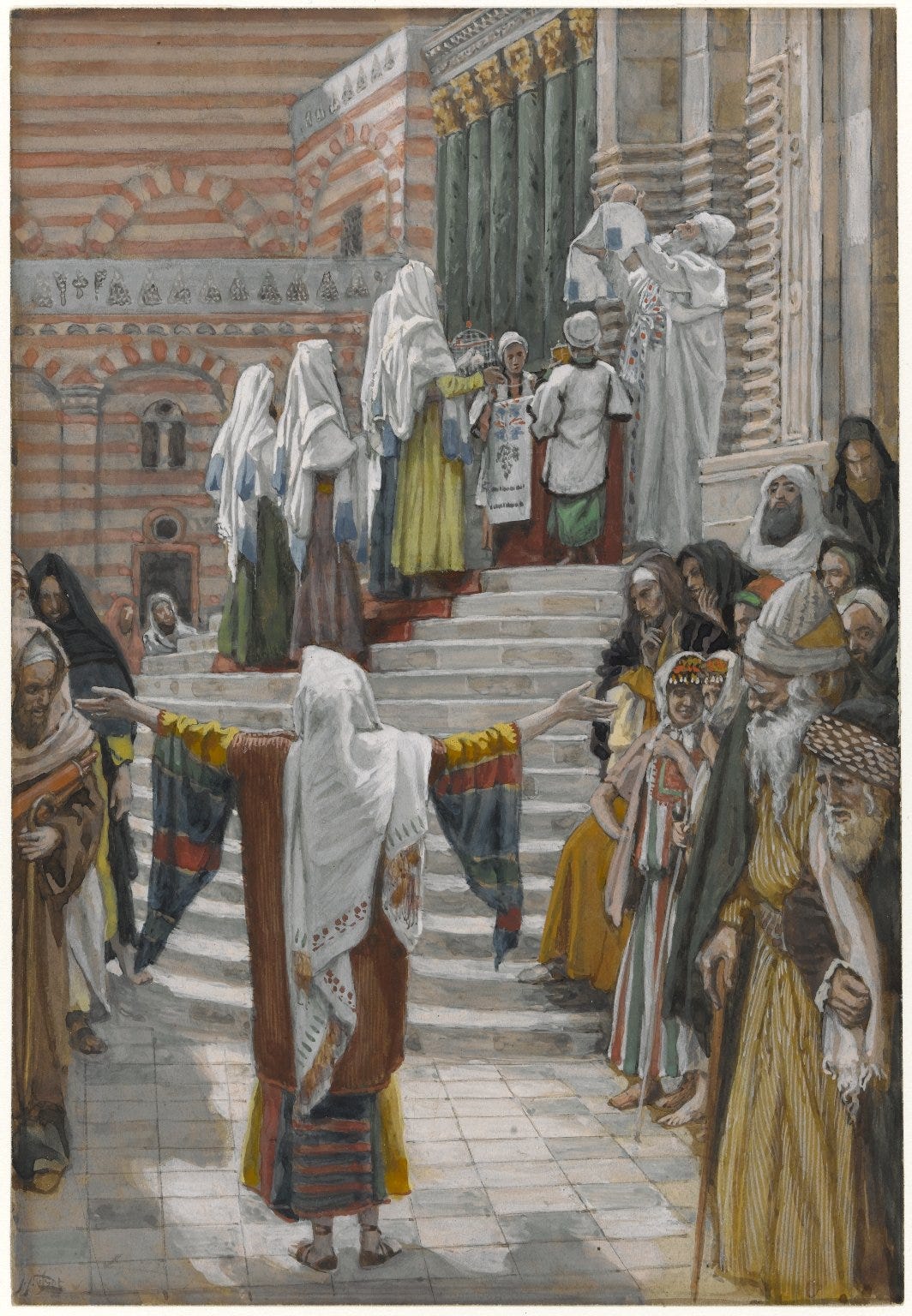

The Prologue begins with a date, February 2, 1802, which is the Feast of Candlemas or the Presentation of Christ in the Temple. When Jesus was 40 days old, he was presented by Joseph and Mary in the Temple, according to Mosaic Law. The prophet Simeon proclaimed that Jesus would be “A revealing light to the Gentiles, the glory of your people Israel.” Candles are blessed on this feast day to symbolically show that Christ is the light to the Gentiles as Simeon announced.

In addition to Candlemas, the Purification of the Virgin Mary is the same day. After giving birth to a boy, women under the Old Covenant were considered ritually unclean for 7 days and needed to wait an additional 33 days before returning to the Temple. During this period, the woman was to wait "in the blood of her purification.” In Scripture, blood is linked with the life of the creature and Deuteronomy 12:23 says “Only be sure that you do not eat the blood; for the blood is the life, and you shall not eat the life with the flesh.” Women were also supposed to offer a sacrifice at the Temple such as a lamb, two turtle doves, or two pigeons according to how much they could afford.

Powers picks February 2 deliberately to enact a sort of anti-Candlemas and reverse Purification on the part of the villains. The villains seek to open the gates of the Egyptian underworld using the Book of the Dead, supposedly written by the god Thoth. Looking upon the book is dangerous and the book itself absorbs the light and warmth from the room.

At first Doctor Romany thought all the lamps had been simultaneously extinguished, but when he glanced at them he saw that their flames stood as tall as before. But nearly all the light was gone — it was as though he now viewed the room through many layers of smoked glass. He pulled his coat closer about his throat; the warmth had diminished too.

For the first time that night he felt afraid. He forced himself to look down at the book that lay in the box, the book that had absorbed the room’s light and warmth. figures shone from ancient papyrus — shone not with light but with an intense blackness that seemed about to suck out his soul through his eyes.

One of the sorcerers, Amenophis Fikee, seeks to speak the Words of Power in the Book of the Dead and invite the god of death, Anubis into his body. They want the Egyptian gods to free Egypt from the British Empire and remake the world. They use their leader’s blood, known as the Master, in the ritual, giving a further reason to view this scene as a reverse feast of Purification. They view Anubis as a Messiah of sorts and the Master is an Egyptian prophet like Simeon is a prophet of God.

“Then,” said the Master in a whisper that echoed round the spherical chamber, “the gods of Egypt will burst out in modern England. The living Osiris and the Ra of the morning sky will dash the Christian churches to rubble, Horus and Khonsu will disperse all current wars by their own transcendent force, and the monsters Set and Sebek will devour all who resist! Egypt will be restored to supremacy and the world will be made clean and new again.”

This ritual is quite literally anti-Christian, bringing darkness and death to the world through the power of Anubis as opposed to Christ being a “revealing light to the Gentiles.” Fikee does bring something through the gate, but things do not go as planned. The gods do not return to rage against the Christian world, but Fikee does become possessed and turns into an anti-Christ figure, killing and switching bodies every Sunday in a perverse sort of Resurrection. By willingly becoming possessed by a demon, he becomes unclean as well thus acting as a reversal of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

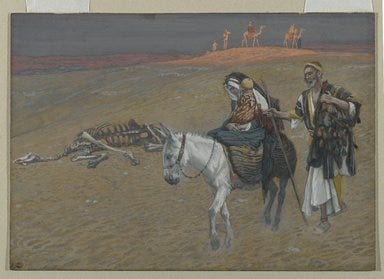

Finally, between Candlemas and the Feast of the Purification, there is a third feast linked to both of them: The Flight Into Egypt. While occurring 15 days after Candlemas, February 17, in the pre-1962 liturgical calendar, the Flight Into Egypt is linked to The Anubis Gates thematically. After the Presentation, Herod declared that all boys under two years old shall be killed because he feared the Messiah. An angel appeared to St. Joseph in a dream and tells him to immediately take his family to hide in Egypt until Herod dies.

The Epistle for the Mass of the Flight into Egypt is Isaiah 19:20-22:

“In those days: they shall cry to the Lord because of the oppressor, and He shall send them a Saviour and a defender to deliver them. And the Lord shall be known by Egypt, and the Egyptians shall know the Lord in that day, and shall worship Him with sacrifices and offerings: and they shall make vows to the Lord, and perform them. And the Lord shall strike Egypt with a scourge, and shall heal it, and they shall return to the Lord, and He shall be pacified towards them, and heal them, the Lord, Our God.”

Fr. William Rock says that the Epistle was selected due to the tradition that the country of Egypt was shaken by Christ’s presence their during His exile. Fr. Rock quotes the Flemish Jesuit, Cornelius a Lapide:

“Because Egypt was full of idols and superstitions. They worshipped dogs, crocodiles, cats, calves, rams, goats, and what not. Christ entered into Egypt that He might cleanse it from this filthiness, and consecrate it to the true God…Hence faith and sanctity so flourished in Egypt that it produced the Pauls, the Antonys, the Macarii, and those crowds of monks and anchorites who emulated the life of angels upon earth, as is seen in Eusebius, S. Jerome, Palladius, S. Athanasius, and the lives of the Fathers. Whence S. Chrysostom, in loc., says, that Christ converted Egypt into a paradise.”

The Master makes a possible reference to Christ’s fleeing to Egypt when he notes that Christianity has somehow barred the doors to the Egyptian underworld. The power of the old gods has diminished since the coming of Christ, but he seeks to open the gates of the dead, and of time, to when they, and he, were at their prime.

“You know our gods are gone. They reside now in the Tuaut, the underworld, the gates of which have been held shut for eighteen centuries by some pressure I do not understand but which I am sure is linked with Christianity. Anubis is the god of that world and the gates, but has no longer any form in which to appear here.”

Candlemas also marks the end of the Christmas season and beginning of Christ’s journey to Easter and the Resurrection.

There are plenty of other references to the liturgical calendar in The Anubis Gates. The dates of various Saints are referred to, September 26 for the Feast of Sts. Cosmos and Damien, St. Mary of Egypt on April 2, St. Giles on September 1, Christmas Eve, The Annunciation on March 25, Easter, and many others.

I will spend some time in the next few posts exploring some of these feasts and how Powers uses them in The Anubis Gates.

Hi Aaron ! Great post! will there be Part 2?