This is the second part of my series where I try to describe what good Catholic (or otherwise) fantasy should look like. In this post, I want to try my hand at discussing how magic should be portrayed in fantasy. As I was writing this, I realized that this is a much bigger topic than I thought! I will probably write more on this later as my thoughts develop.

This is partly a response to a Twitter.com thread my friend, and previous guest on the show, Matthew Scarince (@MScarince) wrote a few months ago on this very subject. He politely asked for my opinion and I decided to tie it into this series. Matthew also writes at The War for Christendom and has recently written an essay for The European Conservative. I highly recommend reading Matthew’s stuff.

If I recall correctly, Matthew was responding to reactions to this comment about Hayao Miyazaki’s latest movie, The Boy and the Heron.

I will not post Matthew’s entire thread, but here is the beginning of his response:

Matthew goes on (responding to me):

Honestly, there isn’t much I disagree with Matthew on his description of magic. He provides three definitions of magic, all of which can be found in The Lord of the Rings.

For example, the elves possess a sort of magic that is rooted in their nature. They would not call it magic and are even confused by what the hobbits are referring to. Elven cloaks and Elven bread seem magical to the hobbits but are natural to the elves. The One Ring is a magic item that renders the wearer invisible to almost everyone. Sauron and Sarumon use their own version of magic to control and subjugate the natural world and the minds/wills of men.

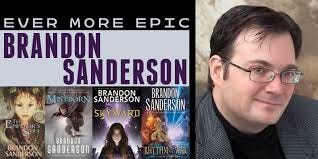

I think the big question is this: Is Tolkien’s magic (or Hayao Miyazaki’s, Wilhelm Grimm’s, Tim Power’s, Gene Wolfe’s, etc.) the same as Brandon Sanderson’s or Jim Butcher’s? Are they just “systems” of magic?

Before we continue, I want to make it clear that I am responding to a certain perception of how authors like Sanderson use magic. I have not read enough Sanderson to comment on his use of magic directly. However, Sanderson has written what he calls, “Sanderson’s Laws of Magic”. He says they are just the guidelines he uses to write his books. Fair enough, but a lot of readers might get the expectation that magic should function like a mathematical equation with all the variables laid out for them.

Matthew stated that “all magic is systematic, it’s a question of whether or not that system is obscure or revealed, complex or simple.” Had Matthew stated that all magic in literature needs to make sense on some level, whether in terms of symbolism, mathematical precision, explicitly or implicitly, I would have agreed. Even the weirdness of the magic in fairy tales has deep symbolic meaning. If the magic is completely nonsensical, then the story would not make sense either.

There is a big difference between what I would call Sacramental Magic and Technical Magic. I am not married to these terms but I think they capture the gist of the two schools of thought I am trying to distinguish from one another. Sanderson distinguishes Soft from Hard Magic but splits them based mostly on how explicit the magic is and how it influences the plot. Personally, I think the biggest difference between the two is that Sacramental Magic is vertical in that it can point up toward Heaven or down to Hell. Technical Magic is horizontal and tends to conflate magic and science into one mode of attaining and using power.

Technical Magic is not a modern tendency. Magical formulas and compendiums of sorcery have existed for centuries. This systematic type of magic is rooted in the mastery of certain techniques, rigid, quasi-scientific rules, and the desire for power. I am not saying that this kind of magic is inherently bad or immoral in a story. I enjoy stories with this kind of magic. It is a lot like technology in that way. However, I think that it tends to overwhelm the story with its special effects and the meaning behind the magic gets pushed to the side. In short, the power achieved through magical means is arbitrary. The fireball might as well be an energy blast or a lightning bolt. It doesn’t really matter.

Framing Tolkien’s Sacramental Magic as a “magic system” is too thin, too simplistic and doesn’t hit the mark. I imagine someone pulling out a black board of mathematical equations or a periodic table of magical spells with Tolkien’s name written on top. That would be like saying the Catholic faith can be reduced to a series of bullet points about dogma and morals instead of a deep Mystery that pulls you further up and further in with the rules embedded within God’s world building.

I don’t want to be accused of creating an unnecessary dichotomy between Sacramental and Technical Magic. They often can be combined to create a story that is both heavy in explicit coherence and can act as a symbol pointing to something higher or lower. Surely, Tolkien does have Technical Magic in his Legendarium, such as that of Sauron and the One Ring as I mentioned earlier. Sauron mastered a specific technique to produce an item used to consolidate his power. Sarumon was tasked with understanding Sauron’s magic and was corrupted by it.

I think magic is at its best when the meaning is hidden with minimal explanation in the plot. The implicit nature of the magic does not mean it is arbitrary or is incoherent. It should still work by the rules embedded in the world building. In fact, the story should be able to function without explaining all of the rules to the reader. The reader does not have to understand the magic to enjoy the story, but the magic should have enough coherence to draw a reader deeper into the tale. It is also my opinion that the most interesting magic has moral rules and costs.

Again, I want to make it clear that I don’t think Technical Magic in a story is “bad”. I tend to think that if portrayed on it’s own, it can tend to be flat. It can still be fun and entertaining, but I think a story needs Sacramental Magic if the author wants to point to something deeper. As Tolkien shows us, these approaches to magic are not mutually exclusive in a story and should be used together for the best effect.

To end this post, I want to use some quotes by G. K. Chesterton from the Chapter “The Ethics of Elfland” in Orthodoxy. I think Chesterton captures the spirit of what I’m trying to describe:

In fairyland we avoid the word “law”; but in the land of science they are singularly fond of it. Thus they will call some interesting conjecture about how forgotten folks pronounced the alphabet, Grimm’s Law. But Grimm’s Law is far less intellectual than Grimm’s Fairy Tales. The tales are, at any rate, certainly tales; while the law is not a law. A law implies that we know the nature of the generalisation and enactment; not merely that we have noticed some of the effects.

…

When we are asked why eggs turn to birds or fruits fall in autumn, we must answer exactly as the fairy godmother would answer if Cinderella asked her why mice turned to horses or her clothes fell from her at twelve o’clock. We must answer that it is magic. It is not a “law”, for we do not understand its general formula. It is not a necessity, for though we can count on it happening practically, we have no right to say that it must always happen. It is no argument for unalterable laws (as Huxley fancied) that we count on the ordinary course of things. We do not count on it; we bet on it.

…

In the fairy tale an incomprehensible happiness rests upon an incomprehensible condition. A box is opened, and all evils fly out. A word is forgotten, and cities perish. A lamp is lit, and love flies away. A flower is plucked, and human lives are forfeited. An apple is eaten, and the hope of God is gone.

This is actually a comment about Friday's Eifleheim discussion, but since Matthew was in on it, at least, I'm pretty sure he's the same Matthew, but it fits in here and I'll add a comment about magic, to make it legit. I thought we had a good discussion Friday, especially because at 83, I learned from your explanation of how you had taught yourself how to read and had applied to rereading Eifelheim. From that, I realized that I had read Eifelheim on the wrong tangent, and, except for our discussion, would have otherwise missed the baby in the bath water.

I also enjoyed the discussions we had with Matthew about how the Medieval age shaped natural science and our current world. That part of our discussion inspired by coming Sunday Still Waters thought verse post for May 19 on my Substack "newsletter". Please visit and read.

On magic: My nine volume fantasy novel, "A Tale of Two Times", makes use a kind of magic which it’s human characters dodge calling magic, but instead call "Goth physics". But Goth physics is actually based on the principles of creation which govern how all beings, especially, in the novel, humans, gods, plants, birds and insects interact. So you could think of Goth physics as the practical art that makes use of intersection of the higher principles of theology, philosophy and science.

So as magic, its practice is the highest, and most deadly dangerous art humans can practice. And the reader will experience the heroine casting a spell on a fallen away Catholic priest.

In the light of your posts on "Guadalupe and the Flower World Prophecy", I can’t resist sharing the following from the seventh volume of "A Tale of Two Times" which suggests the scope of Goth physics in the modern, real world—

“Did you see Tenochtitlan from the Greased Lightning?”

“Yes. I fabricated a Partial Vision by temporal switch-backing over Southern California, to about the time of the Temple’s dedication, which was shortly before the Conquest. In addition to the cup, I possessed a second valid Anchor for the Vision—a relic that I carry, of Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin, to whom I have a special devotion. According to our family tradition, he was a youth among the Aztec worshipers at the dedication of the Temple of Tenochtitlan.

“And Ricardo, in the Partial Vision I saw the young man who would become Juan Diego standing at the edge of the crowd.”

“Was Esmeralda satisfied with what she saw?”

“Esmeralda was stunned by it, and by the incredibly well-organized stream of bloody human sacrifices. She sat silently while we were returning to Ontario, and she left Ontario without a word.”

— The two speakers both practice the art of Goth physics and speak Nahuatl, which is woven into the long story and plays a special part in a major love scene engagement story.

And, thanks again for the Eifelheim discussion.